Assembled here are some quotations from primary sources about the training program that was in place at Disney’s in the early 1930s. (Art Babbitt was part of Sharpsteen’s trainee unit from mid-1932 to early 1933.)

“…There were two of us picked out by Walt to supervise small numbers of beginners. The other man was Dave Hand. We each had small groups of green animators, maybe ten to twelve. By picking up the scenes ourselves from the director, we saved him a great deal of time, because we did all the coaching of these new men. During the course of expansion, Dave Hand was made a director. The sole burden of handling these new men fell upon my shoulders.” – Ben Sharpsteen (trainee unit supervisor, later director) [1]

“…There were two of us picked out by Walt to supervise small numbers of beginners. The other man was Dave Hand. We each had small groups of green animators, maybe ten to twelve. By picking up the scenes ourselves from the director, we saved him a great deal of time, because we did all the coaching of these new men. During the course of expansion, Dave Hand was made a director. The sole burden of handling these new men fell upon my shoulders.” – Ben Sharpsteen (trainee unit supervisor, later director) [1]

“About this time the ‘unit system’ was started as a way to train embryonic animators. The unit heads were like teachers, answering our questions and putting us back on track when we got stuck. I was assigned to Ben Sharpsteen’s unit. Ben had a collection of characters working for him. Besides Roy Williams and me, there was Jack Cutting, Cy Young, Ugo D’Orsi, and many others. We were housed in one large room. It was a motley crew, and Ben was a hard but fair taskmaster. He insisted on good draftsmanship, staging, and action analysis. You had to learn – no shortcuts, just do it right.” – Jack Kinney (animator, later storyman and shorts director ) [2]

“About this time the ‘unit system’ was started as a way to train embryonic animators. The unit heads were like teachers, answering our questions and putting us back on track when we got stuck. I was assigned to Ben Sharpsteen’s unit. Ben had a collection of characters working for him. Besides Roy Williams and me, there was Jack Cutting, Cy Young, Ugo D’Orsi, and many others. We were housed in one large room. It was a motley crew, and Ben was a hard but fair taskmaster. He insisted on good draftsmanship, staging, and action analysis. You had to learn – no shortcuts, just do it right.” – Jack Kinney (animator, later storyman and shorts director ) [2]

“In the process of training new talent, there was such an influx of new applicants that a system had to be evolved to properly supervise their operation. There were assistants of various degrees helping animators, but to make animators of them was perhaps putting too great a burden on the director of the picture. The director of a picture had all he could do to carry out and execute the picture as delivered to him by the story department.” – Ben Sharpsteen [1]

“In the process of training new talent, there was such an influx of new applicants that a system had to be evolved to properly supervise their operation. There were assistants of various degrees helping animators, but to make animators of them was perhaps putting too great a burden on the director of the picture. The director of a picture had all he could do to carry out and execute the picture as delivered to him by the story department.” – Ben Sharpsteen [1]

“In the early days, if you were an animator’s assistant, doing inbetweening and so forth, after you did the inbetween drawings for a scene you had to shoot a pencil-drawing test on the old camera that is now on display on the first floor of the Animation Building, and after hand-developing the animation test and putting it on a revolving drum to dry, you went back to the drawing board while waiting for the film to dry. Then after it was dry you spliced it into a loop and ran it for the animator.” – Jack Cutting (animator, later assistant director, shorts director and manager of foreign relations) [3]

“In the early days, if you were an animator’s assistant, doing inbetweening and so forth, after you did the inbetween drawings for a scene you had to shoot a pencil-drawing test on the old camera that is now on display on the first floor of the Animation Building, and after hand-developing the animation test and putting it on a revolving drum to dry, you went back to the drawing board while waiting for the film to dry. Then after it was dry you spliced it into a loop and ran it for the animator.” – Jack Cutting (animator, later assistant director, shorts director and manager of foreign relations) [3]

“Ben did have a department of younger apprentices. Ben would pick up a scene or a whole series of scenes from a director and then he would farm these out to these apprentices, and he would oversee what they did and help them learn how to be animators. He did that for a while before he began to direct, and I guess Dave began to direct during that time.” – Wilfred Jackson (director)[1]

“Ben did have a department of younger apprentices. Ben would pick up a scene or a whole series of scenes from a director and then he would farm these out to these apprentices, and he would oversee what they did and help them learn how to be animators. He did that for a while before he began to direct, and I guess Dave began to direct during that time.” – Wilfred Jackson (director)[1]

“There was no hiring hall for animators. You could have picked out the best animators in other studios and plunked them in Disney’s, which happened time and time again, and they had to go through a very humble indoctrination: learning how to animate the way we did, learning how to pick your work apart, learning how to diagnose, learning to cooperate with others, learning to accept criticism without getting your feelings hurt, and all those things. We had a saying, ‘Look, this is Disney Democracy: your business is everybody’s business and everybody’s business is your business.’ If you did not have that attitude, you were not going to stay very long. – Ben Sharpsteen [1]

“There was no hiring hall for animators. You could have picked out the best animators in other studios and plunked them in Disney’s, which happened time and time again, and they had to go through a very humble indoctrination: learning how to animate the way we did, learning how to pick your work apart, learning how to diagnose, learning to cooperate with others, learning to accept criticism without getting your feelings hurt, and all those things. We had a saying, ‘Look, this is Disney Democracy: your business is everybody’s business and everybody’s business is your business.’ If you did not have that attitude, you were not going to stay very long. – Ben Sharpsteen [1]

“The only difficulty in ‘adjusting’ to to the Disney approach was that there was no acceptance of slipshod animation (as there had been in New York) and no thought of cost relative to quantity.” – Dave Hand (trainee unit supervisor, later director) [4]

“The only difficulty in ‘adjusting’ to to the Disney approach was that there was no acceptance of slipshod animation (as there had been in New York) and no thought of cost relative to quantity.” – Dave Hand (trainee unit supervisor, later director) [4]

.

“… Naturally when I was given young men of doubtful abilities to use in the performance of my duties, that he [Disney] thrust upon me, I did not realize that the man had a plan far beyond that of training men for the organization. Diagnosing that I was particularly adept at handling green people sparked him into realizing that there was a place for me in his organization where he could profit form that.” – Ben Sharpsteen [1]

“… Naturally when I was given young men of doubtful abilities to use in the performance of my duties, that he [Disney] thrust upon me, I did not realize that the man had a plan far beyond that of training men for the organization. Diagnosing that I was particularly adept at handling green people sparked him into realizing that there was a place for me in his organization where he could profit form that.” – Ben Sharpsteen [1]

“Times were tough, and sometimes you had to suffer to get what was coming to you. Ed Smith, another one of us who worked under Ben Sharpsteen, really did it the hard way. He was living on turnips and bruised fruit – and one day he passed out from malnutrition. He toppled right out of his chair, and Ben came in and found him on the floor. Later, Ben told Walt that he thought the guys going through the ‘tryout period’ should get eighteen dollars a week. Then they could eat at a popular greasy spoon across the street, like everybody else. Walt agreed.” – Jack Kinney [2]

“Times were tough, and sometimes you had to suffer to get what was coming to you. Ed Smith, another one of us who worked under Ben Sharpsteen, really did it the hard way. He was living on turnips and bruised fruit – and one day he passed out from malnutrition. He toppled right out of his chair, and Ben came in and found him on the floor. Later, Ben told Walt that he thought the guys going through the ‘tryout period’ should get eighteen dollars a week. Then they could eat at a popular greasy spoon across the street, like everybody else. Walt agreed.” – Jack Kinney [2]

“While I was handling out work to the beginning animators and Walt was probably giving me a couple of more men, he took the occasion to say, ‘You know, I don’t think that you need to feel you have to do any more animation.’ Of course I thought that if I was not going to animate, then was I worth keeping on the payroll? He could read my expression and he said, ‘You can be just as valuable as that as at animation…'” – Ben Sharpsteen [1]

“While I was handling out work to the beginning animators and Walt was probably giving me a couple of more men, he took the occasion to say, ‘You know, I don’t think that you need to feel you have to do any more animation.’ Of course I thought that if I was not going to animate, then was I worth keeping on the payroll? He could read my expression and he said, ‘You can be just as valuable as that as at animation…'” – Ben Sharpsteen [1]

“[Paul Hopkins] got Walt on statistics, and Walt was trying to achieve an organization that would keep track of what people did and he was trying to get efficiency into the workings of the Studio in spite of the way he worked himself. So the first thing I knew, Paul Hopkins was coming in and asking me questions that I knew he got right from Walt, and it wasn’t long after that I got called to Walt’s office and here was Paul Hopkins and George Drake. My feelings were kind of bruised, but they shouldn’t have been. […] I had been the prime mover of that training program – the art school and all. Walt said bluntly, ‘I don’t want you in that any more. You have plenty to do without that.’ […] I preached the doctrine to those boys; you either learn how to draw or you’ve got no place to go in here. ‘If you want to make a career out of this,’ I said, ‘the sky’s the limit. This man Disney – no telling how far he’s going to go.'” – Ben Sharpsteen [5]

Sources:

- Working with Walt, by Don Peri

- Walt Disney and Assorted Other Characters, by Jack Kinney

- Walt’s People Volume 9, by Didier Ghez

- Working with Disney, by Don Peri

- Walt’s People Volume 3, by Didier Ghez

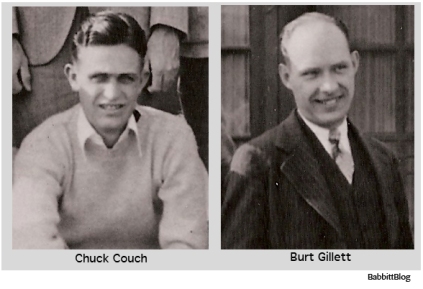

Photos courtesy of Michael Barrier.com, Disney.Go.com and 2719 Hyperion.