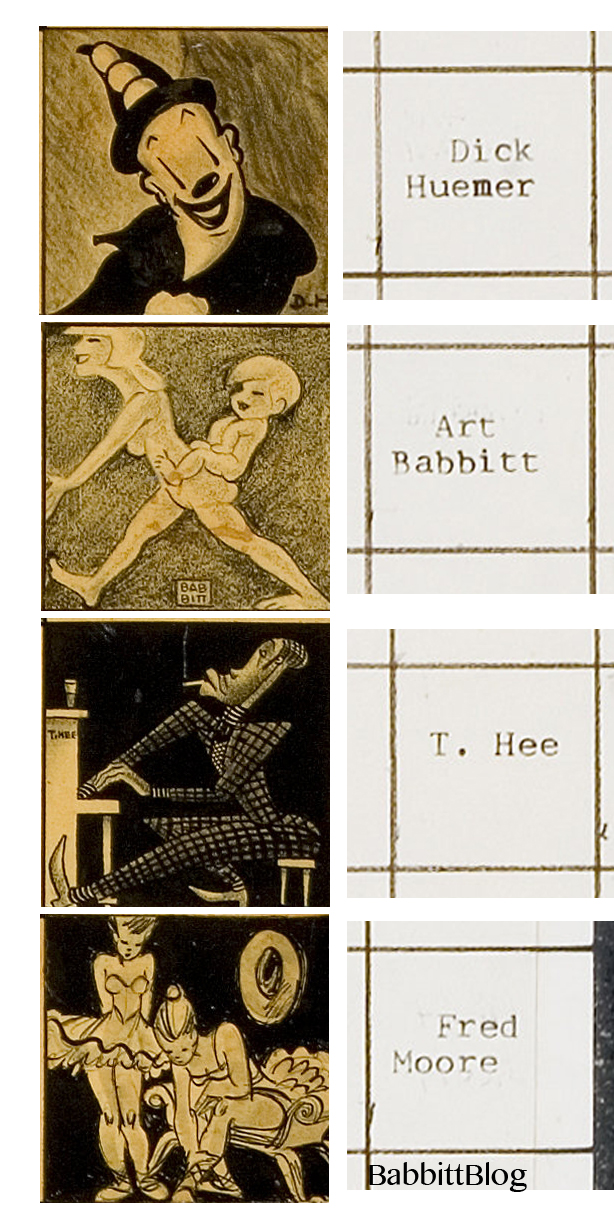

In 1975, John Canemaker asked Art Babbitt what made him want to draw in the first place.

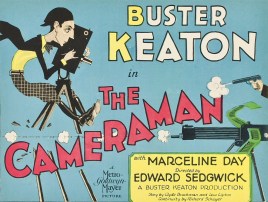

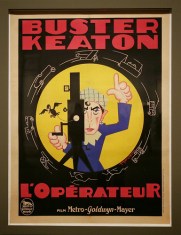

When I was in the second grade in public school [circa 1915], there was a kid who sat across the aisle from me. We all called him Twinkles. And the reason for that was his eyes would blink constantly, and he stuttered, and he had a little indelible pencil about that long, and he would lick the pencil as he blinked and stuttered and then he’d make a little drawing and keep licking the pencil and it always turned out to be the same drawing. And what it was, was a cameraman grinding a hand-cranked movie camera and the cameraman had his hat on backwards and wore puttees.

And god how I wished I could draw like that! And I tried licking an indelible pencil and blinking but none of that worked. He did become a gunman, no kidding. Yeah, Twinkles. Some of my best friends are in the best penitentiaries.

* * *

Sioux City, Iowa seemed like a fine place to raise traditional Jewish family. Arthur’s father was a very religious man and Sioux City had a bustling Jewish population (mostly other Russian immigrants), with synagogues and kosher butchers. From age seven to sixteen, Arthur grew up in the midwestern town with the Jewish and black boys, pulling pranks and having adventures on par with Tom Sawyer.

Sioux City, Iowa seemed like a fine place to raise traditional Jewish family. Arthur’s father was a very religious man and Sioux City had a bustling Jewish population (mostly other Russian immigrants), with synagogues and kosher butchers. From age seven to sixteen, Arthur grew up in the midwestern town with the Jewish and black boys, pulling pranks and having adventures on par with Tom Sawyer.

Prohibition became a federal law in 1919, when Arthur was nearly twelve years old, and Iowa had voted itself a dry state in 1916. According to writer Susan Berman, “In those days Sioux City was called ‘Little Chicago’ because all the gangsters from Chicago used to move in when the heat was on at home.”

The Jewish sector of Sioux City was the childhood home of mobsters David “Davie” Berman and his younger brother Charles “Chickie” Berman. By the 1920s, the Berman gang would rule the casinos and bookies of Minneapolis, and later, Las Vegas. They would keep company with Jewish mob bosses Bugsy Siegel and Mayer Lansky, and they rivaled Al Capone. Older brother Davie was the head honcho, and, according to Davie’s daughter Susan Berman, “Chickie had begun to follow in his brother’s footsteps. He became a Mob torpedo and then started to run gambling clubs in Minneapolis.”

Chickie Berman was Arthur’s age.

* * *

In an interview with Bill Hurtz, Babbitt explains further:

Twinkles became a success. He became a gunman for Chick Berman, another schoolmate of mine, who was in charge of politics, prostitution and gambling in the Minneapolis area. And years later when there was a cleanup campaign in Minneapolis, Chick Burman came to my home and Twinkles was one of his gunmen.

.

.

.

“Twinkles” might be Jack “Rabbit” Badden, a member of the Berman gang who “was a little hard of hearing, and he stuttered,” writes Susan Berman. She later writes,

It was May 6, 1927. According to The New York Times, my father had arrived in Manhattan to engineer the kidnapping for the Mob of a bootlegger named Abraham Scharlin and a partner of Scharlin’s named Taylor. Bootleggers were prime kidnap victims in those days. They had the money for ransom and their associates didn’t go to the police.

Babbitt continued telling Hurtz:

… And Chick and his close associate, Monty – Chick and Monty were the only ones that had a college education in our group – gathered around the fireplace along with a good-looking moll, but Twinkles stayed in the background, near the door, just in case.

_And Chick asked me, you know,“How’d you ever get mixed up in this thing that you’re in? I understand you’re some kind of an artist or something.

_I said, “Yeah.”

_He said, “Well, how come you’re not sitting on silk pillows?”

_I said, “Well, I’m not that kind of an artist.”

_He said, you know, “But what happened?” You know, “What brought this on?”

_And I said, “Well, Twinkles is largely responsible,” and I related the story of twinkles and his indelible pencil.

_And as I told the story, Twinkles became intrigued and he moved up closer, and then Twinkles started to sway back and forth and swivel, and he says, “Sometimes I still do it.”

.

All non-Babbitt info was supplied by Susan Berman’s book, Easy Street. Copyright Dial Press, New York. 1981.