I just saw Saving Mr. Banks, a dramatic re-enactment of author P. L. Travers and Walt Disney’s head-to-head on the making of 1964’s Mary Poppins.

I just saw Saving Mr. Banks, a dramatic re-enactment of author P. L. Travers and Walt Disney’s head-to-head on the making of 1964’s Mary Poppins.

I loved it. Probably due to the Sherman brothers.

As a Disney historian, there were some things that stood out, for good or for ill. So I’ll just label what left the greatest impact on me.

Positive: The attention to detail. From the awards to the magazines on the wall, to the studio lot, to the 1961 version of Disneyland, to Walt’s mid-west homespun dialogue (in the first half of the film), this felt completely true to life. His hacking cough from his smoking habit was there, too – and we even catch a glimpse of him snuffing a tobacco product of sorts, although we never actually see him with a cigarette in his hand. The mythos of Walt’s charm and charisma comes through, and his dialogue is expertly written. Until …

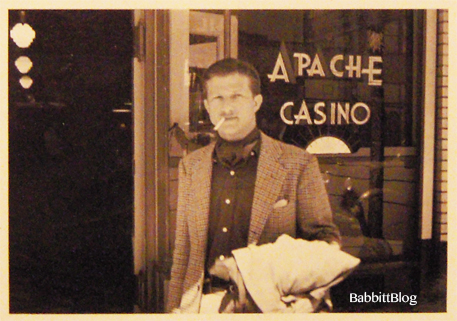

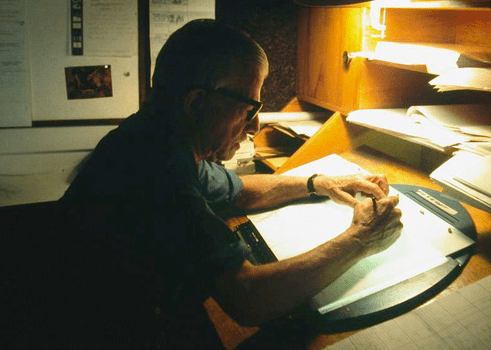

Negative: When Walt shows up at Travers’s door at the climax, he delivers a monologue that feels like a script from his television show. As Art Babbitt said, “When Walt used a three-syllable word, you know it was written for him.” Indeed, candid recordings show Walt using the vocabulary of someone who never finished high school. His final speech to Travers has him in a suit, with his hair slick back, sitting on a chair like he was the self-titled persona he portrayed on television. It did not feel authentic. I doubt the real Walt was as much an armchair psychotherapist as his character is portrayed in the second half of the film.

However, I nitpick. Glorifying Walt is something the Disney company is wont to do, and we should be grateful we even have him saying “Damn” at one point.

The shining moments for me were the scenes in which the Sherman brothers play their original songs to a grumbling Travers. The real Richard Sherman, a living legend and still a dynamo in his later years, was a consultant for the movie, and I have no doubt that these scenes ring truer because of his cooperation.

Not many films make me misty. But when the Shermans warm Travers’s heart with “Let’s Go Fly a Kite” in the writing room, and when their music causes Travers to weep in the Hollywood premiere, there were tears in my eyes. On both occasions.

So I, like Mrs. Travers, was sold the project by way of the Shermans.