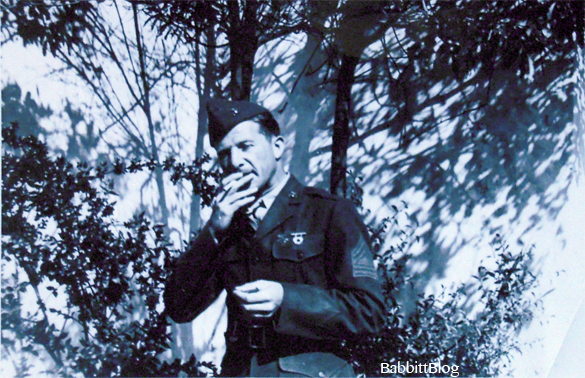

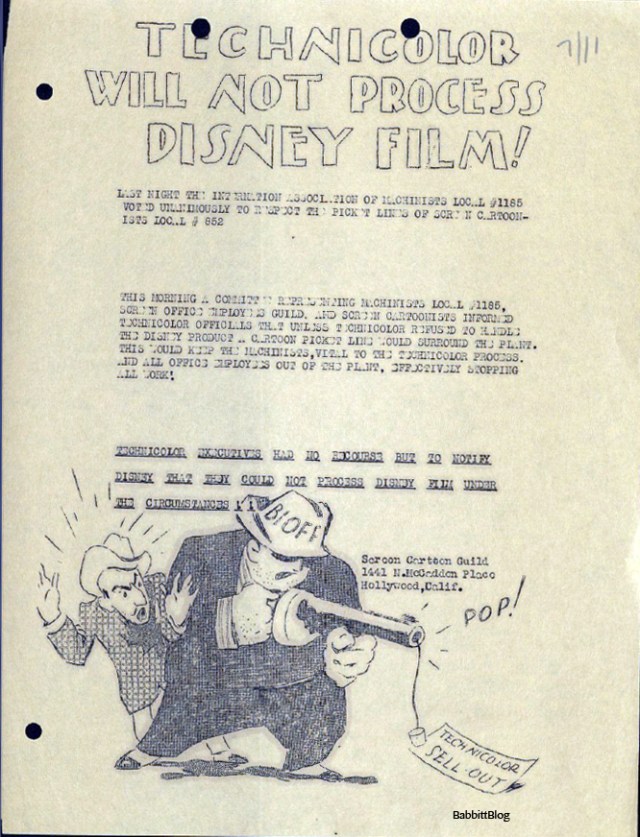

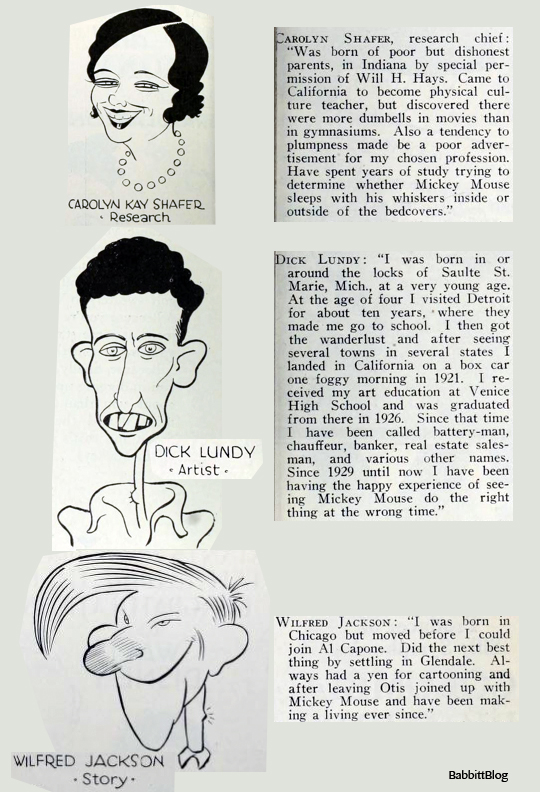

It was 72 years ago today that a picket line formed outside the Disney Studios in Burbank, and hundreds of artist went out on strike. It was Day One of what would ultimately be the largest (and most dramatic) strike in Hollywood history. The strike came as no surprise to Walt –who had even anticipated it in his daily planner — but the impact it had on his studio and his own psyche was completely unforeseen. There was a vote on whether animation supervisors could be part of the strike (directors could not). It passed, and Art Babbitt led the way.

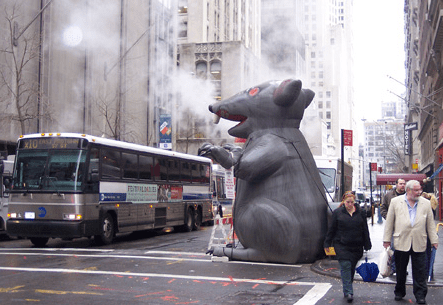

I sometimes wonder what it would take for a young successful professional to go out on strike. I live in Manhattan, and I’ve seen my share of labor discord. It seems like every other week I encounter a big inflatable Union Rat propped outside a building that has been accused of hiring non-union labor.

There seems to be a labor organization for every nearly worker in New York – from the lady who serves you food to the guy who holds the door for you. Not so for the city’s entertainment industry. This became alarmingly true when friends of mine at Viacom (MTV and Nickeldeon) went out on strike in the middle of Times Square in 2007.

Or when my previous employer, Little Airplane Productions, came under fire with the musicians union for negotiating in bad faith in late 2008. It left us to wonder, shouldn’t a cartoon show about music take better care of its musicians?

Or when my previous employer, Little Airplane Productions, came under fire with the musicians union for negotiating in bad faith in late 2008. It left us to wonder, shouldn’t a cartoon show about music take better care of its musicians?

Animation in New York is notoriously sans any type of organized labor. It wasn’t always so – animation writer Allan Neuwirth used to head the New York branch of the Animation Guild, at least until the mid-90s. It disbanded, the argument goes, because the restrictions of hiring union employees was putting too much of a strain on the already floundering east-coast industry.

Not so in Hollywood. Ever since the Disney Strike ended in September 1941, the region has been a union town for animators. With steady projects in film, TV and commercials, a union strengthened the employees’ stance against the employers.

It’s not without its strangeness. Earlier this month I sat in the office of a director for a Nickelodeon show in Burbank, and a project manager came in handing off someone else’s storyboard revisions. He said the PM would one day make a good board revisionist himself. “Why not have him just revise the boards and save the time?” I inquired. “I can’t,” he told me. “It’s union rules.”

Following the rules gets you job security and better working conditions. No animation job I ever worked included overtime of any sort. Like the animators of Snow White, when we had deadlines to meet, we stayed until it got done without any additional pay. One job was generous enough to offer comp time. For another gig, the best we could hope for after 6 o’clock rolled around was a comp dinner. Mathematically, that equaled to about $2.50 and hour, and the regularity of this was expectation was alarming. We discovered that the entire production schedule depended on free late nights. I remember one boss grabbing his coat to leave, smiling with an air of self-satisfaction, as dozens of us stayed at our desks and toiled away.

Unfortunately, unfairness works both ways. I had heard stories of another New York production which offered time-and-a-half after hours, and the employees spent their working days checking their email and did their actual work on their self-imposed “overtime.”

There has got to be a balance of power. No one wants to be taken advantage of, but human nature dictates that scruples take a back seat to basic greed.

Was Walt Disney greedy? Not compared to other company execs today who take full advantage of legislative loopholes. But Walt was trying to run his company not through collective bargaining, but on the whim of his own personality. That in itself is a recipe for conflict.