Let’s talk about the mob for a minute.

Let’s talk about the mob for a minute.

There was a man named Willie Bioff. He was a member of Al Capone’s gang, as was his partner, George Browne. They were both top men of the Hollywood stagehands’ union, the IATSE (International Alliance for Theatrical Stage Employees). Browne, a tall Irishman, was the national head; Bioff, a stocky Russian man, was the head of the southern California branch. In the 1930’s, Bioff’s name became synonymous with Hollywood labor corruption. In the eyes of the Disney company, this man had the potential of being both villain and hero.

So who was Willie Bioff?

So who was Willie Bioff?

Born in Odessa around 1900, young Willie Bioff moved with his family to the outskirts of Chicago. In 1922, he was charged with pandering – i.e. running a speakeasy/brothel – for mobster Jack Zuta, but he never served his jail time. In early 1933 he was arranging to limit the poultry market in Chicago (i.e. making sure some chicken vendors didn’t sell their wares, and getting a cut of those who did). Then he met George Browne. In 1933 Browne was a card-carrying member of the IATSE. They figured out if they could get enough projectionists from a local movie theater chain to threaten a strike, the owner would pay them off. To their reasoning, it would cost the theater more to endure a strike than to grease their palms. A lot more. Tens of thousands more.

One of Al Capone’s top wiseguys, Frank Rio, got wind of this and enlisted them to the gang, kinda by force: It was either join Capone and get protection and a percentage, or drop it all together and get squat. So Bioff and Browne stayed on. In 1934, Rio helped Browne get elected as the national head of IATSE, and Browne hired Bioff as his West Coast representative.

One of Al Capone’s top wiseguys, Frank Rio, got wind of this and enlisted them to the gang, kinda by force: It was either join Capone and get protection and a percentage, or drop it all together and get squat. So Bioff and Browne stayed on. In 1934, Rio helped Browne get elected as the national head of IATSE, and Browne hired Bioff as his West Coast representative.

Now Bioff and Browne did what they were doing before – threatening strikes for stagehands and projectionists unless theater owners and studio heads paid up – except on a much grander scale. In 1935, RKO and Leow’s paid Bioff and Browne $150k. In 1936, Bioff moved to Los Angeles, where he ran a Studio Basic Agreement meeting. It was there that representatives from every movie studio committed to paying him a total of $500k over two years. In 1937 RKO and Leow’s paid him $100k. By the end of 1937, IATSE local 37, the Hollywood branch of IATSE run by Bioff, had spent two years taking $200k from mere members in dues alone.

Whether this was blackmail (Bioff did this against studios’ wishes) or bribery (Bioff cooperated with studios to disenfranchise union members) is still a debate. In either case, Bioff had built up a reputation around Hollywood as the leader of both the absolute largest, and most corrupt, Hollywood union.

The way Babbitt tells it in 1942 is like this: It was in November 1937. His friend and colleague (and fellow liberal) Dave Hilberman showed him an article in Time magazine about Bioff increasing his hold on Hollywood unions. At the time Hilberman was an animation assistant under Babbitt’s best friend, Bill Tytla. Babbitt wanted to stop Bioff and the IATSE from signing up anyone in the Disney studio. At the behest of Bill Garity, the production control manager, Babbitt went to the top of the top: the business head and Walt’s brother, Roy O. Disney.

Roy pointed Babbitt to Gunther Lessing, the studio’s head legal council, board member, and future vice president of the company. Together Lessing and Babbitt formed a group called the FEDERATION OF SCREEN CARTOONISTS. For Lessing, this was an attempt for an informal social organization just to block the Bioff. For Babbitt, this was a chance to create a union to represent the Disney employees.

Blocking Bioff seemed like a great idea: renown columnist Westbrook Pegler published an exposé on Bioff in November 1939 that solidified his villainy in the public eye. This exposé, in part, led to Bioff’s and Browne’s federal indictment on May 23rd, 1941.

For Disney unionists, things went to shit in 1941.

The FEDERATION’s true position – keeping the management’s best interests at heart – became abundantly clear by early 1941. And a bona fide independent union, the SCREEN CARTOONISTS GUILD demanded union representation for the Disney employees.

And then the Disney strike hit on Wednesday, May 28, 1941.

According to many strikers, the energy of the first month of the strike was light. There were hopes for a quick outcome, and there was trust in the company. After a month, though, there was a serious shift.

Bioff was granted a delay of his trial in Washington, as well as permission to return to Los Angeles temporarily. Why?

In a twist befitting a scripted soap opera, the GUILD went into a negotiation meeting the evening of July 1 with Roy Disney, Gunther Lessing, and sitting between them was… Willie Bioff. Roy and Bioff had drafted a settlement deal at Bioff’s ranch earlier that day (some report the previous day), with hope that the strikers would sign.

Babbitt remembered, probably on June 30, being “asked” to get in a car and being driven to Bioff’s ranch. There was Roy, Lessing, Bill Garity, and Bioff himself. Bioff made him a generous offer individually: a hefty payout to just disappear – to take a permanent camping trip, and continue to receive paychecks. Babbitt refused. “I already have more money than I know what to do with,” he said.

Besides Babbitt, the Guild negotiation committee included Dave Hilberman and Herb Sorrell. Sorrell was the business representative of the Guild’s parent union, the Moving Picture Painters Local 644, as well as the Disney Strike’s business manager.

The meeting began with discussions about back pay, and re-hire discrimination, although there were “many inquiries as to why Bioff was in the picture.” Bioff attempted to dictate the terms of the final contract, and also demanded that Hilberman leave the negotiating committee. The Guild left the meeting understanding that an agreement would be further negotiated in the Roosevelt Hotel, a frequent meeting spot for the Strike. Then the company reps returned to advise the Guild that the meeting would not continue in the hotel – but at Bioff’s ranch.

The meeting began with discussions about back pay, and re-hire discrimination, although there were “many inquiries as to why Bioff was in the picture.” Bioff attempted to dictate the terms of the final contract, and also demanded that Hilberman leave the negotiating committee. The Guild left the meeting understanding that an agreement would be further negotiated in the Roosevelt Hotel, a frequent meeting spot for the Strike. Then the company reps returned to advise the Guild that the meeting would not continue in the hotel – but at Bioff’s ranch.

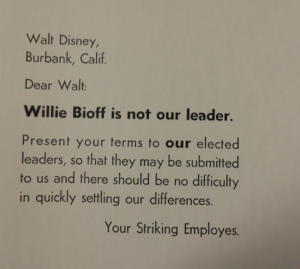

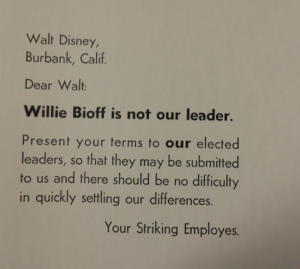

Sorrell called a halt – and addressed the strikers en masse in a huge meeting, to a “thunderous ovation.” They voted unanimously to take no part in any negotiations that included Willie Bioff.

The next day an ad appeared in the daily industry trade paper, Variety:

On July 3, Roy Disney was left with no alternative but to contact Washington DC. At the end of his rope, he requested a federal arbitrator to settle the Strike once and for all.

On July 3, Roy Disney was left with no alternative but to contact Washington DC. At the end of his rope, he requested a federal arbitrator to settle the Strike once and for all.

Arbitrators arrived at the Disney lot. The final agreement between Walt Disney Productions and the Disney Strikers was signed on July 30, 1941, with no help from Bioff. On September 16, work at the Disney company resumed.

So yes, the Walt Disney company briefly had dealings with an indicted felon – the very felon they were trying to defend against. Bioff and Browne were convicted for extortion on November 6 and sentenced to ten and eight years behind bars, respectively.

The Disney studio was able to eventually bounce back, as did Bioff, for a time. In 1942 he agreed to cooperate with federal investigators to lessen his sentence, and he was released in 1944. He joined the witness protection program, and moved with his wife to Phoenix under the surname “Wilson.”

Then on the morning of November 4, 1955 Bioff turned the ignition of his car in the driveway and blew up. The mob had finally caught up with him.

[For more on Bioff, check out Shadow of the Racketeer by David Witwer.]